'Umbrella Night' : A School-Wide Investigation of Peace

Reflections on a Year

by Kendall Nordin

It made sense— with the level of conflict in the world, with the amount of transition we anticipated the community going through– to find an idea for the year’s school-wide investigation, or Umbrella Project, that students could use as scaffolding for their understanding. The previous school year, we had watched young children playing war at a level we hadn’t seen in the few years before. Was it pieces of news from the larger world coming to them? Was it stories from their families or movies? Was it simply a working out of the adult anxiety they’d surely been channeling throughout the pandemic? Was it a shorthand way of being back in connection with each other after a strange time of isolation and masking?

We needed a way to explore the questions we realized they were already asking. We needed an avenue into thinking about our practices around war play and what children need to feel peace in a time of turbulence.

Where can we build resilience? Where can their ideas help us and other grownups to understand Peace?

And so we chose Peace—that simple, that complicated— for the school-wide Umbrella Project.

For me, I started out the year with a question—How do we teach Peace?— and I meant it as both a theoretical and a practical question.

What do we already do that teaches peace? What are ways other people have tried to teach peace? What can we try that might deepen what we already know?

The philosophical underpinnings of the Reggio Emilia Approach ™, the approach that guides Sabot’s programs, are fundamentally driven by a quest for Peace. After World War II, there was a generation of mothers (so the legend goes, but I imagine there were a number of fathers, grandparents and childless citizens sympathetic to the cause) who wanted to build a world where the atrocities and dehumanization of that time could never happen again. Italy had gone through the horrors of Mussolini’s fascism and been front seat to the Nazi regime. In fact, they say, there was a leftover tank and selling the tank was what funded the beginning of those schools with the core intention of making a better world. The basic premise— if we raise our children in ways that allow them to learn their own capacities to hold differences, construct meaning together, listen to each other, represent their ideas, stand in their agency, experience delight, value expression, take action, and be aware of our collective need for each other, then we will have a world that looks different in the end. Loris Malaguzzi’s educational approach was the exact right fit at the right time for those schools. And the approach has traveled around the world. Contextually driven, child-centered, ambitious, collectively oriented– in all those ways and more, it was—and is— a revolutionary model.

At Sabot, the particular thinkers who helped to shape our practice and pedagogy, instilled some habits that are rooted in building peace. Things like: trying to understand children’s intent, moving through conflict productively and not fearfully, representing different ideas and coming to a new understanding together, realizing that everyone makes mistakes and must be supported in making repairs and amends. These begin with the youngest people in our community. In the preschool, when children have hurt one another, we help them move through their feelings and sit down to work it out rather than always imposing an adult driven solution. Eventually they learn that making amends is the best way to help our own bad feelings that come from hurting others. We encourage children to communicate their needs– and we listen deeply to them. We help them listen well in return. We encourage interdependence, kindness, and slowing down. We encourage co-construction of peace in the mess of conflict. We hold our understandings with complexity and build tolerance for uncertainty.

This year, I watched students of all ages wrestle with questions like

What is peace? How does peace feel to me? Where do I find peace? What do we do when there is conflict? In the spring, when some of the classroom work culminated in displays and exhibitions for our Umbrella Project Celebration, it painted a picture of possibilities for creating peace:

- We build and produce signs to remind each other of how to be with each other, in peace.

- We notice and wonder at the natural world that may not always be “peaceful”— birds eating worms, red blood cells fighting white blood cells.

- We celebrate music and fire and community and how being together can bring peace.

- We give gifts, just because.

- We find modes of economy that are based in what people can give and what they need, not on arbitrary value controlled by profit.

- We think about whether peace is a lasting condition— or one we have to perpetually work towards.

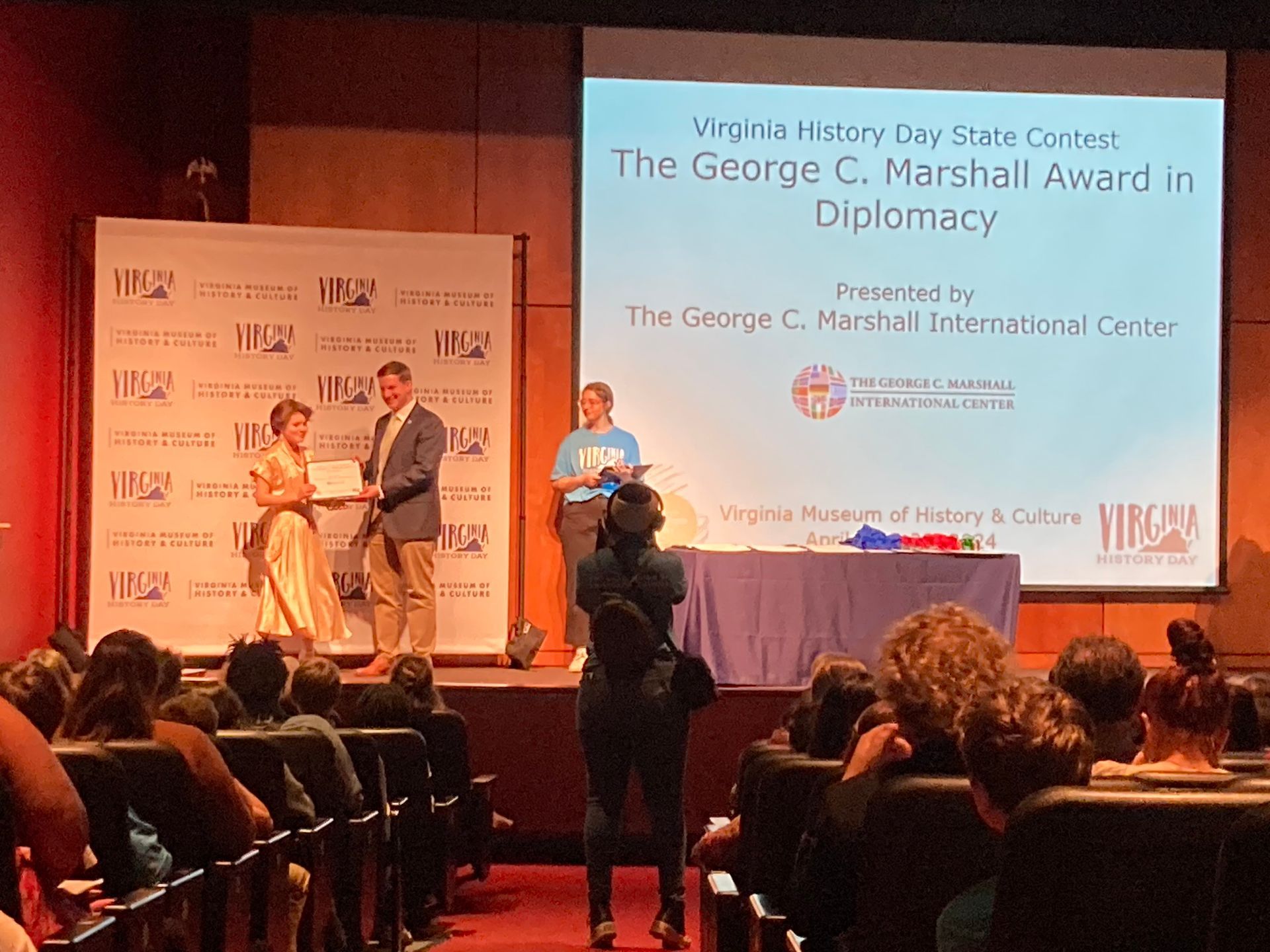

- We learn about our collective history and teach others skillfully.

- We learn to make something big together, bringing all of our ideas into something richer than any of us could have done on our own.

- We marvel at all the ways patterns can emerge in our environment and all the ways we can describe and know them.

In terms of what I was trying to understand this year, how do we teach peace?, Umbrella Night put front and center the notion that none of us can do this alone. When we step back and take in the school’s work as a whole and the children have time to see each other’s work, then we see a nuanced understanding of peace. Without all of their insights together, we be tempted to think that teaching peace is having children do only the one thing.

There are times when what is called peace is not peaceful. As in a frozen conflict or a negative peace, the absence of conflict. The children leaned into metaphors that alluded to the fact that conflict is a part of our lives. They were able to see complexity in blood cells and the garden. There are always opposite forces or counteracting forces, just like a see saw. Peace may seem like it can be stillness— and sometimes that is true— but peace is always a process. People point to meditation as an example of peace. For anyone who has a committed practice, they know that sitting can be very un-peaceful. The goal is not achieving perfect stillness, but returning again and again to the hope. It is in the effort that we learn how to inch our experience closer to that still point.

I am grateful for all that I was able to explore and watch the children grow into this year. We know that the Umbrella Project not only serves to provide a direction for the children but also for teacher’s research and for families’ involvement. Teachers apply things they learned in previous year’s shared wisdom to the coming years and new ways of practicing. Based on what I saw on Umbrella Night, I can only imagine what a treat it will be to see how these ideas evolve and take shape in coming years.

Kendall Nordin has spent a large portion of her life teaching and working with all ages of learners in many different settings—from a one-room schoolhouse in the Costa Rican cloud forest, to the library at the top of a fjord in Alaska, to museum trips with young children in Washington, DC. She started learning about the pedagogical philosophy of Reggio Emilia in 2006. She holds a BA from Georgetown, an MFA from RMIT in Melbourne, Australia, and is currently working towards an MDiv at Starr King School for the Ministry. Most recently, she served as Sabot's Preschool Pedagogical Coordinator.

SHARE THIS POST