Complexity and Error: Science

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: The Role of Error in Science

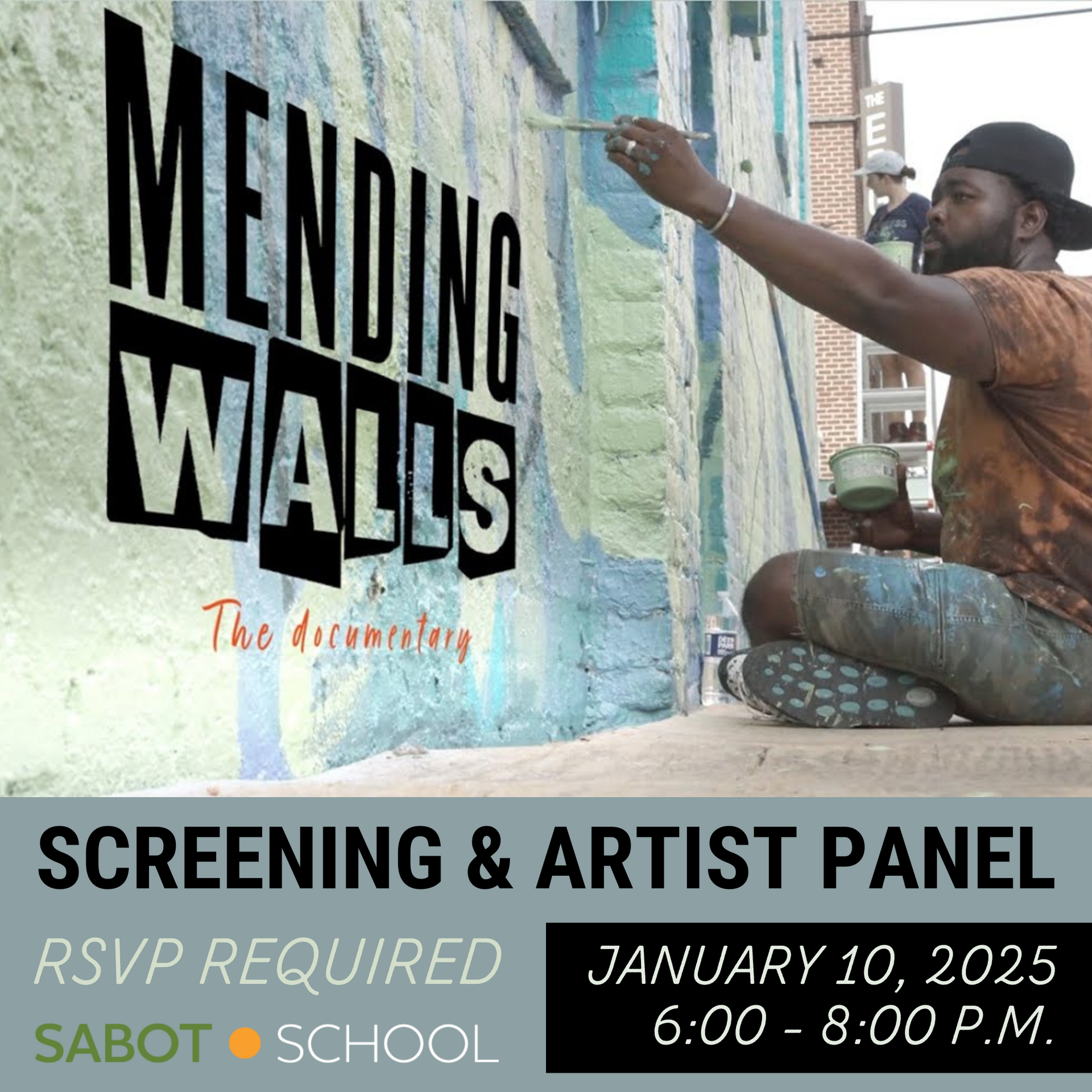

This automated soccer-ball kicker required multiple design iterations – and much trial and error – before it was a success.

Continual forward progress in learning is sometimes an expectation of teachers and parents alike. It’s easy to think of learning as a continuous, upward trend of mastery. Is this a reasonable expectation? Is that how learning really happens?

In fact, true learning — true understanding — results from a constant process of problem-solving, of trial and error, of two steps forward and one step (and sometimes two, three or more!) back.

I am reminded of a student’s VJAS ( Virginia Junior Academy of Science ) project from a few years back. The project required the construction of a contraption that kicked a soccer ball. The design started as a simple block of wood, pivoted at one end and powered by a spring. It did not look much like the action of a human leg nor was it effective at “kicking” the soccer ball. Multiple redesigns, many of them successful and many of them failures, finally resulted in a hinged leg, complete with soccer cleat, multiple springs and a release mechanism that triggered at just the right time to mimic the kicking action of a human leg. It was a complex machine, built on the back of multiple revisions, many of them abject failures!

Advancing our understanding of the natural world requires us, as scientists, to push boundaries, to make mistakes and to respond to them. The goal is to improve our hypotheses and theories and ultimately make scientific breakthroughs that better explain the world around us.

(Continue reading after the jump for a look at the soccer-ball-kicker in action!)

Although it continually evolves, we have used the scientific method to manage this process of discovery and understanding for a very long time. Often taught as a linear process, the scientific method is not linear, but iterative , with each step being visited multiple times during an investigation.

Why is this necessary? Shouldn’t a process that has been used by so many be smooth and efficient? Not so much. The truth is that scientific investigation is a complex process, and, as with any complex process — especially one being implemented by a beginning scientist — there are going to be mistakes and errors along the way. Both learning about the natural world and following the scientific process follow the rhythm of two steps forward, one step back.

Long-term trends, short-term deviations

In science, we look for trends and patterns to help us explain changes in observed phenomena or behavior. But it is rare that these trends are continuous or complete. For example, this chart shows that there has been a clear and obvious increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air since the start of the Industrial Revolution, and particularly since 1950:

Carbon Dioxide Atmospheric Concentration since the Industrial Revolution

But look at the trend more carefully: at a more granular level, you see that the upward trend is anything but smooth. In fact, there is a continual pattern of “two steps forward, one step back”, as each year, the deciduous forests of the northern hemisphere shed and then grow new leaves:

Fluctuations in Carbon Dioxide Concentration Each Year

Like this hidden pattern, the learning process may look like a continuous, upward line from afar, but reveals something very different when studied up close. At Sabot, we expect there to be bumps and dips in the learning process on a regular basis. As teachers, we expect students to make mistakes in seemingly simple areas as they focus on the complex and challenge themselves to deepen their understanding. We expect that as they reach for greater understanding, they will follow paths that may seem like the right one – but turn out to be a blind alley. What we help them to do is to both allow them to follow these leads, teach them to recognize when they turn out to be mistakes, and point them towards another path that leads onwards and upwards. It is why we engage in long-term projects in science that allow students to flounder at times while they try to reach the next level of understanding. It gives them the opportunity to make mistakes and work out a solution or correct them before being assessed.

In the end we look at each student’s progress over the long term — for the whole project, the whole trimester, even their whole time in middle school. If we focus too much on the errors that were made today or this week, we might miss the bigger picture. And if a student doesn’t feel comfortable making those errors and blundering down a few blind alleys, they may never end up finding the paths that help them choose a voyage of discovery and growth.

Below: the soccer-ball-kicking contraption at work!

Jan 7 2013 039 from Sabot Middle School on Vimeo.

The post Complexity and Error: Science appeared first on Sabot at Stony Point.

SHARE THIS POST