Complexity and Error: Math

Teachers and parents can sometimes make the mistake of assuming that once our students have learned something, then we can expect that learning to be “set” — ingrained, permanent, and readily available for accurate retrieval. On a math test, we might wonder how a student managed to tackle a complex math problem, but arrived at a wrong answer as the result of overlooking a simple and apparently obvious addition error.

In fact, however, when students are tackling new or complex tasks, the cognitive demands of that work can often result in exactly that kind of calculation error.

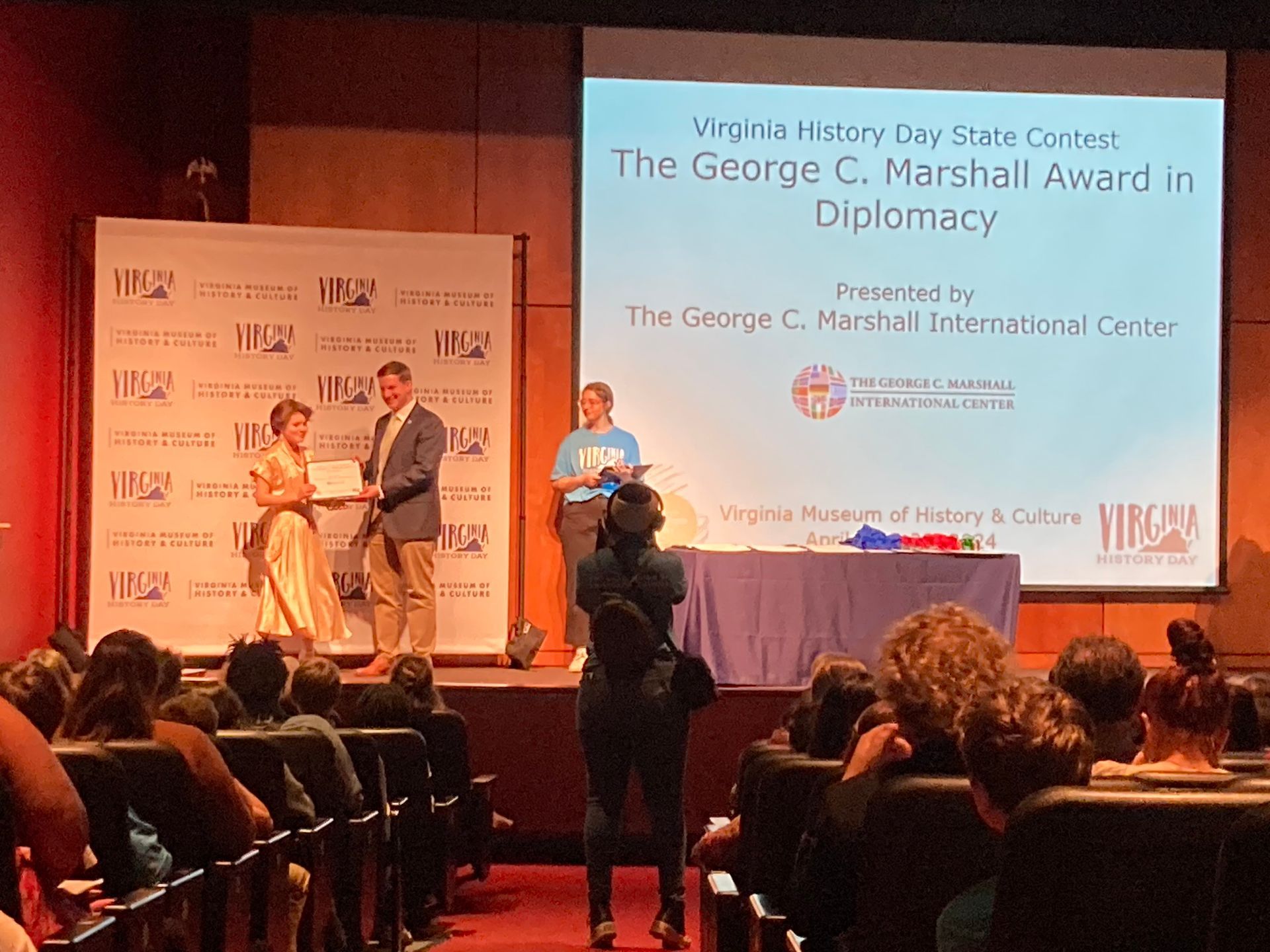

A simple error in scale during a complex investigation of graphing.

In the example above, as the student was working on the complexity of graphing, they forgot about the basics of scale that they had mastered previously. At first glance, it might seem as though this student doesn’t understand scale, but upon further observation it becomes obvious that the student is focused on the new, more challenging skill of graphing, and the “easier” skill of scale did not receive their attention. It is not that the student has failed to learn or has forgotten basic math facts — their brain is just consumed by more difficult concepts present in the problem. Teachers learn to recognize this kind of error as a sign that students are actively engaging with new concepts.

Interestingly, recent research suggests that making mistakes generates electrical activity in the brain even when we are not consciously aware of the error. As summarized by Stanford University professor of mathematics Jo Boeler , this research indicates “that the brain sparks and grows when we make a mistake, even if we are not aware of it, because it is a time of struggle; the brain is challenged and the challenge results in growth.”

In mathematics, it is valuable for students to play with numbers, ideas and concepts, and to test out ideas. Through this process, they can figure out why something works or doesn’t work, and then have the ability to apply what they have learned to other new and unfamiliar problems. This ability, transfer of learning , is an essential indicator of true learning and understanding. If students are simply given a procedure and told what to do, they can get the “right” answer when presented with similar problems — but they may develop no connection to or understanding of the bigger concept at work. Teachers and parents can encourage or discourage the way young mathematicians are able to view, incorporate, and learn from their mistakes, if we can recognize “productive mistakes” when they happen.

The post Complexity and Error: Math appeared first on Sabot at Stony Point.

SHARE THIS POST